The Compassionate Mind Foundation and Compassion Focused Therapy

The following article by Dr. Paul Gilbert is reproduced from the international UK Compassionate Mind Foundation Webpage, and it addresses the key elements of CFT. The original can be found here.

© P Gilbert 2007

The Compassionate Mind Foundation was set up to help promote the scientific study and the application of compassion to a range of human problems. A guiding principle of the Foundation is that our human potentials for creativity, love, altruism, compassion, but also for selfishness, vengeance and cruelty are all linked to the way our brains have evolved to solve various challenges to survival. For example, parental love and care – so vital to the survival of many mammalian offspring evolved as solution to a range of threats (e.g., predation, lack of food and harsh ecologies). Hence there are systems in our brain that evolved to be attentive and take an interest in offspring, recognise and respond to their distress calls and behave towards them in nurturing ways. These systems form the bedrock for later evolved extensions of caring behaviour and enable us to have concerns for others and want to care for them. As we will see later these are key systems from which the various attributes of compassion can emerge.

However, residing in the same brain are systems that are concerned with self and kin survival, and seeking out things that we see as necessary for our own prosperity or those close to us. Threats and harms to ourselves or those we love, and blocks to the things we are seeking/wanting can activate a range of defensives responses that can include; fear, sadness, despair, frustration, rage and violence. When the brain is in the mode of ‘self protection’ other of its potentials (including those for compassion) can become less accessible. It is difficult to feel kind to people we are very angry with. So the brain is full of a mosaic of potentials that create patterns of activity. We know that is operates via generating patterns because if we use techniques that allow us to see how the brain operates when engaged in various tasks or experiencing different emotions, these variations are associated with different patterns of activity in different brain areas. So our motives, feelings, thoughts and behaviours arise from the activation of different patterns in the brain. Also of course, when we experience brain patterns associated with anger or anxiety we think and feel differently than when we experience brain patterns associated feeling safe, cared for and compassion. Note also something that is implied here. The evolution of our capacity for care and love for some people (e.g., our families or friends) can turn also fuel aggression to those who might or have hurt them.

Modern research is beginning to illuminate the genetic basis of these dispositions and the way our social relationships, from the cradle to the grave, shape our brains and value systems, and thus dispositions to create different patterns of activity in our brains. The more we understand these processes the more we can understand how different patterns in our minds are created. This knowledge allows us to stand back and explore ways to ‘manage the potentials in our evolved brains’ such that we can advance certain dispositions and potentials over others. We are something of a tragic species because our minds are easily taken over by ancient brain systems that give rise to fears, passions, and desires for selfenhancement and selfprotection – including the protection and enhancement of others we are close to. Although these potentials have had evolved functions, they can also be the sources of the best and worse in us. If fact we suggest that cruelty can flourish when compassion falters.

A Biopsychosocial Approach

Efforts to specifically foster ‘compassion patterns’ in our brains require the integration of knowledge in many domains. These include genetic (e.g., we know there are genes that regulate a hormone called oxytocin that in turn affects affiliative, caring and soothing behaviour); neurophysiology, (e.g., we know there are key brain areas, especially in the frontal cortex that enable us to have empathy for others and to inhibit more primitive aggressive behaviours); psychology (e.g., we know there are certain beliefs and types of selfidentity and defensive or safety behaviours that can advance or inhibit the desire and pursuit of compassionate values); social relationships (e.g., we know that when people feel loved and valued they are less likely to behave in defensive and cruel ways than when they feel threatened, excluded and alienated). Cultural values (e.g., we know that the cultural values in Buddhist monasteries give rise to different cultural patterns to those say of the Roman or Nazi empires – which of course impact on the flourishing or inhibition of compassion). Ecologies (e.g., we know that people adapt to their ecologies and those that are relatively safe and benign create different cultural values than those that are filled with threats and uncertainties).

The Foundation therefore focuses on integrating knowledge from different fields of study, each of which has it own array of complexities. The general term for this approach is called biopsychosocial meaning that a full understanding of any basic human disposition (and to use a technical term ‘their phenotypes’) comes from understanding the interactions between the different domains of our being. You can read more on this basic approach to compassion in Gilbert’s edited book on Compassion published by Routledge in 2005 and Davidson and Harrington’s edited book on Compassion published by Oxford University Press in 2002.

The Evolved Mind: How it Links to Cruelty and Compassion

A basic aim of the Foundation is to explore how to specifically foster a ‘compassion pattern’ in our brain and in social relationships. The idea that we need to do this, because our evolved brain contains some highly destructive potentials, is not new (Goleman, 2003). The Buddha did not know anything about the evolution of brain systems yet over 2,600 years ago he recognised that human minds are filled and bombarded with powerful passions, desires and emotions, from which can emerge our dispositions for cruelty and suffering. The mind, he argued, is unruly and without training is governed by primitive passions, the seeking of shortterm pleasures and efforts to escape and avoid, disappointments, pain and suffering. However, developing insight into the arising of the thoughts and passions within us (mindfulness) and the cultivation of compassion can be a major antidote to suffering and cruelty to self and others.

Today we know that many of our difficult emotions such as disgust, anger, rage, anxiety fear, and terror are all rooted in the systems in our brain that have evolved over millions of years. Indeed, we can see many of these emotions in other animals in certain contexts. This is because these emotions have had protective functions and those animals that had these potentials survived and left their offspring behind more often than those who did not.

The problem for us is that some of our new evolved competencies such as our extraordinary capacities for selfawareness, selfreflection, reasoning, imagination and planning have created both the advances of civilisation but have not freed themselves from our underlying evolved motives and passions. For example, we know that a fear of snakes and spiders was highly adaptive. These fears can make individuals highly sensitive to detect ‘crawly” things and have an anxiety response. However, such dispositions are less helpful today in the U.K, but remain with us and can become a source for phobias that can be quite debilitating. Consider that fat foods and sweet foods were a rarity in our evolved past and this rarity meant that seeking them out wherever they existed was adaptive. However, doing the same when we have supermarkets is not. The constraints were, in the past, provided by the environment; whereas now we have to try to contain our own natural desires for sweet and fat foods – obesity, heart disease and diabetes can the result if we do not. This raises the problems in that given the way our brains have evolved over the last few million years and the cultures we have created, many of our basic dispositions need new systems for their control. Indeed the ‘rule of law’ is a culturally invented process that seeks to contain individuals acting out their own self interests and retaliations.

You can see that a key theme here is that a compassion focus is knowledge based – illuminating the way that some of our dispositions for both compassionate and very non compassionate (cruel) behaviours are linked to the various dispositions that evolution has laid down in our brains. When we stand back and look at our history we see that life and humans have not evolved is some Garden of Eden. Indeed without the challenges in nature much of the variety of life may never evolved at all – change, as Darwin perceived so clearly, come from challenges harsh though these are. The struggle for survival operates at multiple levels, in the way we find our food, how we protect ourselves from other animals doing likewise, how we defend against various bacteria and viruses, and the fact that our lives as short, our bodies decay and end in death. All these are part of the journey of DNA from the simplest to the most complex life forms.

Adapting to Threats

The fact of the matter is that life on this planet is highly threatening and dangerous. 99% of all species who ever existed on this planet are now extinct and for much of human evolution life was precarious. Some have estimated that we could have been down to as low as 700 humans in the whole world and a species related to us called Neanderthals didn’t make it through the last Ice Age. Only their bones and artefacts remain as a memory of their passing. In a way compassion begins by recognising that a lot of our mental mechanisms are survival orientated trying as best they can to enact strategies that maximise our survival and protect us from harm and leave genetic relatives. However, many of our own old programmes and strategies that make us sensitive to certain kinds of threat, haven’t caught up with the fact that we are living in a totally different world – which is partly of our own creation.

If some of our basic emotions and fears are triggered these can then drive thinking and behaviour. For example, we are no longer content with the odd fight to deter or get revenge but can plan sadistic acts and weapons of mass destruction. And because we have got the technologies to do that we are potently highly dangerous. However note that this is not really our fault – we are simply going along with what our brains have evolved to do none of us choose to be bourn to have brains like we have. So humans, have an intelligent and insightful brain that can be literally taken over by these basic emotions. ‘Thinking’ is then recruited to serve our desires for vengeance or selfprotection, not subdue them. In fact the history of the last few thousand years is part of the history of the struggle between the dominance of defensive emotions and aggressive strategies against those of compassionate ones.

We can take the same approach to our social behaviour and the way we treat each other. As noted above, we have evolved in a very threatening environment. It has been by looking after each other that we have survived to get to where we are today. This ‘looking after’ has evolved in different domains, for example a key one is in the parent/child relationship. But recall also that our anger to those who might hurt our loved children can release very aggressive feelings and behaviours in us.

The Experience of the Self

We, of all the species, are probably the only ones that have a ‘sense of self’ and are acutely selfaware of what we want, what we feel and try to make and shape our self identities. The evolution of selfawareness and our competencies for certain types of thinking and reasoning have made us the dominate species on the planet and we may even hold the fate of many others in our hands. Yet this development and evolution of our selfaware and thinking minds in the universe has a number of costs.

Human survival has depended on the good relationships we have with others. Shamed or rejected individuals would not survive or prosper. Because these outcomes have been so bad for our survival it is very easy for them (or the risk of them) to activate our defensive emotions such that we fly in rages if criticised or become trapped by anxiety or fall into lonely despair. We are evolved to strive for a sense of belonging, acceptance and respect in the minds of others because over millions of years these have been highly conducive to our survival an prosperity. In fact much of our everyday thinking is related to creating feelings and impressions in the minds of others. So for example if you think about how your would like your lovers, friends, bosses and all those that are important to you, to think and feel about you, your primary concerns is that in their minds you exist as someone desirable, likable or talented. Animals can pick up on threat or rejection cues, but they cannot locate symbolic reasons for being ignored, rejection or hostility from others; that is they probably can’t appreciate that one can be attacked or rejected because one is judged by others to be ugly, untrustworthy, immoral, stupid or lazy. Nor, in contrast, can they reason out that they can be cared for by mother, or wanted as a sexual partners, or sharing friend with because others see them as attractive, trustworthy, moral, clever and hardworking. Humans, however, have evolved high level cognitive, meta cognitive and symbolic abilities that not only give rise to a sense of self but can also attribute intentions and feelings governing the actions of others (e.g., ‘I believe she does not like me because she sees me as bad, ugly, untrustworthy’). Thus humans need to know (or at least have reasons for) why others accept or reject them, how to entice others to like them, and evaluate themselves such that they can predict the qualities of self that others will like, value, or reject or attack.

This is why we so easily adopt values and belief systems from those around us. From the cloths and fashions that we choose, to the religions we adopt – each is influenced by our needs to feel that we fit in with others and are seen as belonging to a certain group. We want to be ‘like others.’ Our efforts to do things that we think our parents, bosses or Gods will be pleased with are to court their good feelings towards us. This helps us feel safe and prosper. These social needs for safeness, and avoidance of rejection, direct how and what we think about ourselves and others. However it can have very destructive aspects. Chinese foot binding and female circumcision for example emerge because of the way social groups create certain values and then individuals endorse and enact them to avoid shame and rejection, and earn acceptance or prestige. So we recognise that people’s sense of identity and belonging are linked to their cultures and traditions. People can easily feel threatened if these come under attack. The point about this is that the very sense of the kind of person we are, and the kind of person we want to be, is linked to the social groups we operate within.

So our survival has depended upon belonging to groups, developing close ingroup ties and being mutually supportive. These evolved dispositions to identity with a group or family and then defend its interests and ingroup ties may have helped us through the last ice age where we lived as relatively small isolated groups. Think how much the issue of group identity and efforts to defend one’s group and even assert one’s group over all others, has played a part in human history. The fact that humans make quite easy and clear distinctions between ingroup and outgroup is related to the fact that our very survival in the past, may have depended upon those decisions. Today however this basic psychology can be a threat to us as we enter a world of competing group interests and the break down of communities into mega groups serving ‘market forces’. Any analysis of compassion and fostering a psychology of nurturance must address this basic psychology.

What about within group relations? Well for us, as for other animals, there is also within group competition for resources (e.g., for food and the comforts of life, sexual partners and friends, and social position). We compete for our social places. Also, like other animals, we have dispositions to form authority and dominance hierarchies, distinguish between the more or less powerful or talented, and then engage in submissive and appeasing behaviour to the dominants. We see this basic way of thinking about relationships and behaviour reflected in many walks of life, through the adoration of certain leaders, including various Gods, through to simple structures related to sports. The evolutionary motives to both belong and to follow do not seem to be problematic and yet these are the source of some our most problematic behaviours.

We are confronted with a series of social motives and dispositions relating to both belonging but also asserting oneself over others, that form the basis for potential problems in the modern world. In a moment we are going the look at the challenges of cruelty, but above we have identified some key psychological process that are going to figure in this analysis. Compassion and a compassionate psychology require clear insight into the way evolution has handed us some rather difficult problems in the way our minds work that we will have to confront. This is neither our fault nor evolution’s – it is just the way it is.

The Challenge of Cruelty and Callousness

If compassion is rooted in desires to alleviate suffering and prosocial behaviour (Dalai Lama, 1995, 2001), then its antithesis is cruelty. The Concise Oxford Dictionary (Allen, 1990) defines cruelty as: “1. Indifferent to or gratified by another's suffering. 2. Causing pain or suffering, esp. deliberately.” (p. 279). We might define some intended, harmful acts as ‘evil’ but evil is a complex judgment that many find problematic (Baumeister, 1997; Shermer, 2004; Straub, 1999, 2002; Zimbardo, 1995). One person’s view of an evil act can be another person’s justified retaliation or defence. The Foundation will use the language of ‘cruelty’ and related concepts and stay with the dictionary definitions. We need to think how a disposition for cruelty emerges from other of our social potentials and the fact that the brain operates ‘in patterns’ – turn one pattern on and another can get turned off or made inaccessible.

Although Buddhism sees compassion as basic to our nature (Dalai Lama, 1995; Goleman 2003, Wang, 2005), in the West, we have long held the view that our basic natures (our evolved dispositions) are to be more cruel than kind (de Waal, 1996). It is easy to see why. Violence, abuse, bullying, undermining and callousness in schools, work and in the home, stalk the lives of many (Schuster, 1996). Taking abroad sweep of history reveals the last few thousands years as marked by wars and atrocities; the mass crucifixions of the Romans, the invention of the torture chamber, the Holocaust, Stalin’s persecutions and ethnic cleansing, our incessant search for better weapons and the arms trade are but a few examples of the State and religious use of terror (Millett, 1995; Straub, 2002). Daily we are appalled by the violence, raping, atrocities and the sheer cruelty of various conflicts in the world. These behaviours are so common that they point to universal potentials that can, under various conditions be activated. Rather than thinking in terms of evil we need to think how our history as been scripted from primate brains with their basic survival strategies, that became ‘intelligent.’ It is of course a complex story but one that may also reveal clues on how to foster compassion and the obstacles that will emerge when we try.

In regard to the interaction between social and evolutionary influences, people can behave cruelly when focused on tribal defence or expansion, have a strong sense of ingroupoutgroup, and where the social structure perpetrates hierarchy authorities and ‘obeying orders.’ Indeed, as Kelman and Hamilton (1989) argue many of our cruelties are linked to acts of obedience, protection of groupidentities and submissive efforts to impress the higher ranks. The nature of the relationships between groups also help define cruelties. When small, subordinate groups engage in intimidatary violence against a dominate group the former can be seen as criminal and cruel, but when large elite nations engage in similar actions they are defined and justified differently. Hence, specific acts are defined in different ways depending on context, and who is doing the defining (Scott, 1990). Because we have evolved with a brain that is highly attentive and responsive to dominant elites, leaders can do much to shape social values and behaviours. Consider what the Middle East would be like today if they had been able to find a Nelson Mandala or a Ghandi. In a fascinating study, Green, Glaser and Rich (1998) looked at the historical records for the link between unfavourable economic conditions (e.g., high unemployment) and hate crimes (lynching and beatings) directed at minorities. Current wisdom had it that with increases in relative poverty, envy and frustration build up, leading to increases in hate crime. But this link proved weak. Green, Glaser and Rich believe that an important factor in the rise of hate crimes is the emergence of leaders, or power elites that direct and orchestrate violence for their own ends or reasons. Although hatred of the outsider is an all too familiar aspect of our behaviour, such forms are typically mixed in cauldrons of social values that literally cultivate it. As Gay (1995) points out social groups and their leaders can do much to foster fear, hatred and general beliefs of one’s own group’s superiority and justification for cruelties. Thus cultural and traditional belief systems, the manner by with leaders and subordinates interact and manipulate power and control, and the way we so easily develop and adopt beliefs through our groups are key to any full analysis of the cruelty and the blocks on compassion.

One of the key issues for human beings is to acknowledge, come to terms with and seek to counteract, is the fact that the evolved mind has basic potentials to seek to maximise its own resources. Before the advent of agriculture and large group living such ‘selfish’ motives were constrained by the group who enforced egalitarianism (Boehm 1999). However with the production of surplus, groups could grow larger and then resources could become unequally shared and controlled. Within a few thousand years we had found that our new social structures, which we praise as civilisation, could bring to life ways of thinking, feeling and relating to others that would turn off all semblance of compassion. Indeed the Romans saw compassion as a weakness. Human history is full of Empires that have arisen from the subjugation of people and slavery. The Egyptian and Roman empires were entirely dependent on their slave classes that claimed the lives of hundred of millions. The underlying psychology is to use others to create power, wealth and comforts for oneself. In large groups with subgroup elites these motives are no longer constrained by threat of shame and exclusion. In effect subordinates lost there power over the dominants. When the motives for self-enhancement dominate our states of mind ‘the other’ can become but an object to fulfill our own needs and our feelings of compassion are tuned off.

In 2007 Britain marked the 200th anniversary of the ending of institutionalised slavery that claimed over 20 million lives. It is disturbing to think that just a few hundred years ago the cruelties of slavery were rarely considered. While our cultural values are changing and outright control over another human being is increasingly seen as morally unacceptable, there still remains serious problems with slavery in the world and forms of bonded labour that are not much different. Some estimates put the figure at over 8 million people still subject to slavery and bonded labour many of them children. Consider also the scale of human trafficking for prostitution and drugs.

Today the drive for competitive advantage, efficiencies and profits can drive the behaviours of our international corporations and government to more callousness and away from a compassion and caring focus in our cultures (Bakan, 2004). At times we seem trapped by social systems we helped to create. The force of economics and technological change seem to sweep us along with what seems like little choice other than to hand over control to the market place that cares not at all about our mental states or wellbeing. We may come to live in more efficient worlds but they may be so bleak and exhausting, and lack any basic joy, caring or sense of community, that few actually want to live in them. We now worker longer hours not shorter ones; our retirement ages are extending not shortening; in every walk of life people are noting that the demands on them (and fears of falling behind and exclusion) are increasing so that they feel unable to have the time to do their jobs properly or gain a sense of satisfaction from them (Bunting, 2004). The exploitation of the planet and climate change are spins offs of the way our cultures have fostered and rewarded individualisation and selfenhancement at the expense of nurturance. For some the costs of human progress are cutting across our basic human needs for belonging, social commitments and affection. In an increasing competitive world few governments have found ways to square this circle. Maintaining one’s competitive advantage and the fear of the consequences of falling behind dominates our thinking. We seem powerless to break out of the race. Yet at some point we will need to think of how to balance economic realties with creating social worlds that are conducive to human happiness and well-being. There is sufficient evidence now that after a certain point wealth creation and striving for ever increasing efficiencies are not conducive to happiness and can in fact make us callous and ill.

Our entertainments too are riddled with a fascination for cruelty. From the gladiatorial games to more modern day fantasies in Hollywood, cruelty stalks the imagination. A visit to any local video shop will show this fascination with cruelty and violence. All these of course are textured, not by open admission of cruelty, but with various psychological manoeuvres that offer justifications for why our actions are not cruel but are deserved, warranted, sanitised and acceptable (Bandura, 1999; Beck, 1999; Gay, 1995). The Romans claimed a passion for bravery, glory and contempt for death, while today we claim a desire for excitement and thrill. Some claim that in this fascination with cruelty we are trying to face deep fears of our own mortality and violence by seeing them played out on others. In this view the more frightening and out of control our lives seem to us the more attracted we are to these forms of entertainment. Whether this is true of not (at least for some people) there is increasing concern and research on the way our engagement with violent and sadistic entertainments (in books, films and video games) stimulates our brain patterns in certain ways which are not conducive to the patterns for compassion.

The role of the media also plays a part here pandering to people’s cruel and anxious fascinations in order to sell their papers. In their book on prosocial behaviour Hinde and Groebel, J. (1991, page 3) note that sadly aggression is often perceived as `more interesting' than prosocial acts. News makers know this effect and use it, with the consequence that violence has a much greater probability of being reported than prosocial acts. Even scientists may regard aggression as more stimulating, as a more common behaviour: until recently, the scientific literature on violence and aggression by far exceeded that on prosocial behaviour, cooperation and altruism

Against this human history, predilection, and current social tides it is easy to feel overwhelmed, disheartened or outraged. Unfortunately, these understandable responses can become sources for a closing down of our minds to the realities, keep our heads down and just keep going, avoidance, despair, or the justification for the next round of callous actions or cruelty. We do not lack understanding of the biological, psychological, social and cultural bases for cruelty (Bakan, 2004; Baumeister, 1997; Milgram, 1974; Shermer, 2004; Straub, 1999). Nor is it difficult to see why humans want to selfimprove and have the comforts of life, and are reluctant to give them up (Galbraith, 1992).

What has been captured in the forgoing is a brief exploration that to promote compassion (which counteracts cruelty and indifference) we need a biopsychsocial approach. We cannot go back to the small isolated groups of thousands of years ago that constrained selfishness, environmental exploitation and rewarded sharing. New processes for harnessing compassionate values are required. We have made some progress in some areas such as in the rule of law noone wants to live in warlord dominated environments (other than warlords, of course). Indeed the whole nature of political debate is concerned with the relationships of individuals to groups and to the State – notions of personal freedom, issues of bestowed rights and of social responsibilities. The struggles to articulate and assert these values and subdue the exploitations of the few over the many have been intense and are on going, both within nation states and between them (Lewis, 2003). Justice emerges in part as the wish to constrain exploitations and the uses of power, and legitimise deterrents and punishments. Compassion relates more to emotional concerns with promoting wellbeing. Justice depends on an agree set of rules and concern with fairness while compassion resides in feelings such as sympathy and empathy. Clearly the psychologies that motivate concerns with justice and those for compassion interact. For example, deterrents such as torture and hanging drawing and quartering changed as they come to be seen as inhumane. Hence compassion can influence processes of law and deterrents. It is, however, a matter of some complexity, debate and research to consider how these overlapping but different psychologies, using different aspects of out minds, blend together so that they facilitate and feed each other.

If we consider the concept of ‘social responsibility’ then people can approach this with a mindset of duty or fairness, or fear of punishment for breaking contracts but also because of emotional commitments based on carefocused feelings. It is possible that teaching compassionate values, the reasons for them, and developing social cultures that share and reward them is a major shift in focus that we now need to explore. Hoffman (1991) argues that caring behaviour can be promoted when we bring children's attention to it. He suggests:

One thing moral education can do is to teach people a simple rule of thumb: Look beyond the immediate situation and ask questions such as "What kind of experiences does the other person have in various situations beyond the immediate one?" "how will my actions affect him or her, not only now but in the future?" and "Are there people, present and past, who might be affected by my action?" If children learn to ask questions like these, this should enhance their awareness of potential victims of their actions who are not present and to emphasise with them to some extent. To increase the motivational power of empathic identification, children should also be encouraged to imagine how they would feel in the absent victims place, or to imagine how someone close them would feel in that person's place. (p. 288).

These issues pertain to many aspects of our behaviours not just in the training of our children. They are simple but also the most profound of questions. The research questions here are what helps and hinders people actually asking themselves and giving time for feeling and reflection on these questions? How do social contexts affect us in asking these questions? How do fear of market losses and the pursuit of profit personally and in business, or international trade agreements extinguish these questions in our minds? How common is it for those who stand outside a conflict (and the threatfocused psychologies conflicts activate) to understand that the protagonists are locked in psychologies of anger and revenge that will lead nowhere but more human misery, more victims, more fear and revenge.

It is for these and many other reasons that the Foundation is concerned with the promotion of compassion are all levels of human activity and functioning. This is why the Foundation considers the challenges of how to harness our potentials for a compassionate psychology to flourish with clear insight into the difficulties involved (related to our evolved and social constructed minds). Developing compassion involves developing our understanding of the nature of compassion, and an emotional commitment and self-identity for compassion. Many now are turning to studies of prosocial behaviour and compassion as major processes to address cruelty and other of our problems that we now face in the world (Davidson and Harrington, 2002).

Compassion

The new challenge for humanity

If we are to create a more humane world, we must first study more fully the basic processes involved in compassion and compassionate behaviour, the way compassion is and antidote to cruelty and indifference to suffering, and the way compassion is a source of happiness and good health. Second, we must continually work to develop the compassion focus in our own individual lives, our family and child rearing environments, schools, health systems, businesses and economic systems, and political discourses. To do this we must understand what promotes and nurtures compassion in these various domains and what blocks it. In the years to come we hope that many people, from different disciplines, will come to focus on the complex interactions between our dispositions for cruelty and compassion.

What is compassion?

Clearly to be able to promote compassion we need to understand it and its constituent elements. Importantly there is a long history to such endeavours. Buddhism defines compassion as a nonjudgemental open heartedness to the suffering of self and others with a strong desire to alleviate suffering in all living things (Dalai Lama,1995, 2001). Developing compassion for self and others is central to the processes of bearing and reducing suffering. Compassion in this approach can emerge with mindful practice (a change in awareness of the nature of mind) and by combining mindfulness with various mediations and actions (Leighton, 2003). Buddhist concepts of compassion are based on the idea that we suffer because we are ignorant of how our minds really are.

Compassion has been key to other spiritual traditions and can underlie forgiveness as in Jesus’ famous statement “forgive them for they know not what they do.” Modern science is giving a new twist to this sentiment as we become more aware of just how much our emotions, desires passions and selfidentities are routed in evolved systems of the brain and shaped by social contexts; that we are not fully aware of. Science is revealing just how ignorant we are (and have been) of what guides and regulates us in both conscious and nonconscious processes.

Western Approaches: Over the last few thousand years, Western philosophers have also given much thought to the issue and value of compassion. Aristotle suggested compassion “is a painful emotion directed at the other’s misfortune or suffering” (Nassbaum (2003p. 306). Nassbaum (2003) suggested three key cognitive elements to Aristotle’s view summarised as:

The first cognitive element of compassion is a belief or appraisal that the suffering is serious rather than trivial. The second is the belief that the person does not deserve the suffering. The third is the belief that the possibilities of the person who experiences the emotions are similar to the sufferer (p.306)

Nassbaum (2003) also notes that we can feel compassion for a person who may not appear to be suffering at that moment (someone who has lost insight due to brain damage or is in a coma) because we understand what they could have been and what they have lost, even if they do not. This is also key in the process by which we can have compassion for someone who has no insight into what they could become.

Compassion can thus relate to having knowledge that the other may not have, but which if they did have could help them. In many ways psychotherapy implicitly operates from this principle, thus leading to psychoeducation (e.g., on the evolved nature of our emotions and needs, or how our thoughts affect our emotions and vice versa, the problems of avoidance etc) and the provision of tasks that can promote change and growth.

Compassion also links to a Buddhist notion of common humanity – that we all find ourselves on this planet constituted by a set of genes and shaped by our social conditions – none of which we choose. Via mediation we are able to grasp this sense of common humanity that we are all seeking to avoid suffering and to prosper guided only by our evolved minds and social conditioning. We can also grasp that in each human being is a struggling consciousness and had we been born with the same genes and life circumstances as someone else then ‘I’ would be ‘him or her.’ Thus meditation helps us break down the barriers between ‘us’ and see the very nature of conscious in a new way. This kind of ‘conscious raising’ and deep insight can however take years of practice. It is possible that there are other ways, that seek to specifically harness our minds ‘compassion abilities,’ that can be helpful in creating compassion patterns in out minds.

An Evolutionary and MultiFaceted Approach:

Although evolution has laid down basic systems in our brains from which various forms of cruelty can flourish it has also made possible our dispositions for compassion. Compassionfocused abilities and competencies can be linked to particular evolved mental mechanisms.

1. Motivations to care (provide help, support, protection and warmth) for others are a crucial first step in compassion. The early sources of these are probably from caring behaviour directed at infants – a basic mammalian trait (Bowlby 1969, 1973; Geary, 2000). Later, because mutual support and friendships carried advantages in survival and helped us deal with various threats, care and concerns were extended to others of various ages and needs. Care providing is costly however so people make decisions as to who and how much care to offer – but that is a different point. Here we just note the motivational systems underpinning desires to be helpful to others.

Caregiving motives, which may have first appeared on our planet within the parent infant interaction have of course undergone significant extension and modifications. Human infants die without care. But we now know that the caring behaviour of human parents are multifaceted, complex and change over time. Human parental care involves not only basic provisions of protection and food but an array of psychological inputs that help the infant have experiences of affection in the interaction, develop empathy for their own emotions and develop a sense of self and a self–identity. Indeed the quality of care including how a parent responds to the needs and displays of the child, how they take an interest in, play with, and encourage the child; how they show their pleasure in their interactions with the child, and how they socialise the child – all affect how the brain matures (Schore, 1994). Key brain systems in the frontal cortex that help us feel empathy for others, and regulate our more basic emotions, and mature slowly after birth, can be affected by lack of love and various hostile or non caring interactions (Gerhardt, 2004).

2. Brain systems have evolved that are responsive to being cared for and about (feeling safe and soothed). For example babies and infants cannot calm themselves but a parent’s affection can calm an infant. This element to compassion is important because evidence suggests that when we feel loved, wanted and included we tend to feel safe. In these social environments potentials for empathy and compassion are harnessed (Gilbert, 2005). In harsh and socially threatening environment however it is the threat and self defensive emotions that are needed to be developed. Clearly then potentials for compassion can be nurtured in early life

3. We have evolved abilities to have insights into the experiences of self and others; that is to have insight into their feelings, styles of reasoning and needs. This allows us to consider the intentions and reasons behind other people’s behaviour – a technical term for these abilities is ‘theory of mind’ – to understand that people act according to how various aspects of their minds are working. The preparedness to use these abilities to understand others is a cornerstone of compassion. When we will feel anxious or angry or are focused on our own selfpromotion, our interest in being empathic can falter.

4. We have evolved abilities to reason, imagine and plan how to promote the wellfare of self and others (or their down fall). These can be linked to a selfidentity and personal goals. Although our selfidentities are partly constructed to fit our social groups and value systems (because we want to belong, fit in and be valued) selfidentities can, to some extent (and there is debate as to what extent) be chosen too. If we grow up in certain environments we may develop selfidentities that focus on getting ahead of others and we are motivated by selfpromotion goals. We direct our attentional focus and learning to these goals. However we could choose a compassion goal and try to find ways of behaving they help us feel in tune with that selfidentity.

The various factors that impinge on each of these and their interaction are of course complex and here we have only focused on key motives, abilities and attributes that enable us to be compassionate. However these do not yet specify the nature of compassion.

Social Mentality Theory and Compassion:

Social mentality theory (SMT) was developed as a way of thinking about how different aspects of our minds are activated in different patterns to create different types of relationship (Gilbert 1989, 1995, 2005). SMT suggests that individuals cocreate social, reciprocating roles for caring, cooperating, competing and sexuality. Each role requires the activation and organisation of different components of mind. Thus when caring for others we are emotionally moved by the needs and feelings of others, are motivated to care, and try to work out how best to care. Threatfocused emotions, and desires to threaten or harm the one we are caring for are usually turned off. In contrast when competing with others or when others are seen as threats or enemies our minds are patterned in different ways. Carefocused mechanisms are turned off and desires to harm or subdue others are turned on. Thus SMT stresses the importance of patterns of brain activation that are activated in the creation of differ types of relationship. This is why we use the term compassionate mind to depict the combination of different elements of our minds coming together to form ‘the compassionate mind’.

So we have argued that compassion emerges when our minds seek to create care focused interactions. Hence it recruits, and is patterned by various competencies of the care giving, social mentality. Armed with these insights we can now think about the core constituents of compassion. These qualities are referred to as the compassion circle.

Components of Compassion from the Care Giving Mentality

Sensitivity

Sympathy

Distress tolerance

Empathy

Care for well being

Nonjudgement

Care for Wellbeing: This involves a motivation to be caring of other’s distress and also to promote their wellbeing. It captures the Buddhist notion of motivated concern. We can direct these desires to all living things and the environment. When directed at the self, the self becomes focused on genuine desires to nurture the self. Caring for the self is about looking after and is rather different to the more competitive goal of promoting the self for competitive advantage.

Distress and Need Sensitivity: This involves a capacity to be sensitive to the nature and complexity of distress; to be able to read emotion cues and have an awareness of distress. It also involves the emotional ability to be sensitive to other people’s needs and requirements that will help them prosper. When directed at the self it involves the ability to be sensitive to one’s own distress and needs, rather than condemning, ignoring or avoiding them.

Sympathy: Sympathy is the ability to be emotionally moved by both the distress and the joys of other people. Some people with psychopathic difficulties can be empathic and even distress sensitive, but emotionally cold to these sensitivities. We can lose feelings of sympathy for others or for the harm we do them if we see them as threats to ourselves. Sympathy for the pain of our friends is easier than for our enemies and indeed seeing our enemies suffer may be felt positively. One reason for this is because too much sympathy (when we need to defend ourselves or only focus on our own self interests) could stop us taking protective actions. So we can see that when threatened our brains may actual turn off the ‘sympathy module’. Sympathy to self is the ability to be emotionally moved by the suffering of one’s own life, rather than dissociated for it.

Distress Tolerance: Research has shown that we can at times feel overwhelmed by the distress of others, become distressed ourselves and feel that there is nothing we can do to help. We become unable to tolerate their distress because of what it stimulates in ourselves. These are unpleasant feelings that we might try to avoid. As some might say “I can’t watch the news as it is just too upsetting.” The ability to stay with (rather than turn away from), tolerate and think about the distress of others is an important element of compassion. Also the level of distress, if we really thought about things, could be just to overwhelming. For example in 2006 The Lancet estimated that 650,000 had died in the Iraq world. To stop and think about or find out and truly enter into the suffering of each one of those deaths cause would be overwhelming – so we do not think too deeply about them. Compassion then requires that we are able to tolerate distress but not be so overwhelmed that we simply switch off.

Compassion is not necessarily about rescuing though it can be. Therapists may struggle to tolerate painful feelings in their patients and engage in rescuing behaviours, or act out their own countertransferences. It is possible for people to be emotionally sensitive and sympathetic but to feel overwhelmed by distress and thus avoidant or try to be over controlling.

Our abilities to be compassionate also mean that we need to be familiar with our own minds and have selfcompassion. For some people inner feelings, thoughts, memories, fantasies or situations, can be frightening and they engage in a range of safety strategies to try to avoid or rid themselves of them. Buddhist, and recently, many western therapies note that trying to rid oneself or avoid painful emotions or situations can be problematic. Learning how to accept, tolerate and ‘bear’ painful emotions, reduce emotional intolerance and avoidance can be key to change. Distress tolerance related to oneself involves abilities to tolerate aversive emotions (including grief and sadness), alter negative thoughts about emotions, and reduce avoidance. All exposure type therapies are to help people tolerate painful things and learn that some of the catastrophic fears they may have about engaging with ‘the feared’ are unfounded. What to tolerate and how to tolerate and what to change is thus at times complex, but rest on the principles of advancing growth and wellbeing. If one’s hand is hurting because it is too close to the fire it is useful to remove it rather than just bear it – thus tolerance should be purposeful and needs to be ‘wise and mindful.’

Empathy: Empathy involves emotional resonance with the other, trying to put ones self in their shoes, feeling and thinking in a similar way but also with cognitive awareness about the reasons for others peoples’ behaviour, intentions, feelings and motivations. This is related to theory of mind. It is related to ‘understanding the reasons for...’ It is the opposite of projection. Genuine empathy allows insight into what is helpful and healing and is the foundation of wisdom. Because it is in some sense ‘knowledge’ based, it provides the framework for what Buddhist psychology calls skilful action.

NonJudgment: Nonjudgment is the ability to engage with the complexities of people’s (and our own) emotions and lives without condemningly judging them. Focusing on the processes of knowledgeable empathy can help nonjudgment. For example, we know we are created via a combination of our genes, learning experiences and social contexts. We realise that had we be bourn two thousand years ago in Rome we might be happily looking forward to the Games and watching people kill each other. We know that people can become trapped in mental states of depression, fear, paranoia or vengeance, propelled along by powerful emotions that shape our experiences of the world. We did not design these but they exist within us because of our evolved brains and social contexts. Thus much of the way we feel and act are in many ways ‘not our fault’. This is not to then to deny responsibility but rather to understand these processes, and what we need to do to help ourselves become mindfully and compassionately responsible for our actions. It is via becoming compassionate (rather than condemning) and harnessing compassion qualities of mind that opens the door for understanding the passions (functions and strategies) of our evolved minds and taking responsibility over them.

Warmth: This is an emotional quality of gentleness and kindness that operates through all of the above. Warmth is a difficult quality to accurately define but it involves non threatening whilst having a genuine caring orientation. Commonly, experiences of warmth are noted by nonverbal communications and interpersonal manner. People who are viewed as warm as usually seen as safe and nonthreatening but not dull or passive – they have a calming impact on the minds of others. Feeling threatened or frustrated commonly turns off warmth. The same is true of our relationships with our inner selves.

The compassion circle above offers but one way to conceptualise compassion. If we decide to harness, practice and develop these qualities of mind in social contexts that support and reward them then just maybe we can direct our efforts to our mutual well being. This is not a new story but an old and ever changing one.

Overview

The scientific discoveries of the twenty century has open our eyes to the fact the we are evolved beings. This takes some coming to terms with. Until now we have been largely unaware of the forces (genetic and social) that shape the experiences we consciously have. This is slowly changing. The challenge of the next century is taking our new knowledge of ourselves and working out together how best to use this knowledge for the benefit of humanity. Who knows what our cultures will be like in a hundred years from now if we seek to bring a compassionate focus to our child rearing, schools, businesses, governments and international politics.

Understanding Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) and

Compassionate Mind Training (CMT)

We can focus our attention and thinking and ruminations on our fears and shortcomings and be propelled in despair. Rather than treat ourselves with care and compassion the potentials for anger and hatred can be directed at the very essence of ourselves. If fact we now know that a lack of abilities to feel compassion for the self and with tendencies to suffer shame and selfcriticism underpin a lot of human misery and psychopathology. When people feel depressed or anxious they can feel that others do not care much for them and are likely to be critical and rejecting. In addition, people may not care much for themselves either. So both the outer world and the inner world turns cold and hostile – there is nowhere to derive any sense of safeness, comfort or support.

For these people many forms of therapy have been tried with various degrees of success. However the Foundation suggests that a specific focus on developing compassion for the self can be one way to stimulate brain patterns that help people counteract brain patterns associated with anxious and despair states of mind. This is often easier said that done but efforts to help people develop selfcompassion has lead to compassion focused therapy and compassionate mind training (Gilbert 2000, 2005; Gilbert and Procter, 2006). The basic theory for this approach is routed in the same kind of biopsychosocial approach that we noted above. The ‘techniques and procedures’ involved in the therapy are derived from a wide range of evidence based interventions that address peoples styles of thinking and imagery, the processing of emotions, and various behaviours such as avoidance and safety behaviours. We will explore the therapeutic aspects shortly.

In general then we see compassion as a key potential in our minds that we can learn to harness, develop and hone. This can help us become more nurturing in our relationships to the environment, animals, our social relationships, intergroup relations and our sense of ourselves This document will outline a compassion focused approach to psychological therapy. I shall be using two terms: Compassion focused therapy (CFT) and compassionate mind training (CMT). CFT is derived from the evolutionary model of social mentality therapy (Gilbert 1989, 1995, 2005a,b). It offers ways of focusing various therapies (e.g., BT, CBT, DBT) on the development of selfsoothing and selfnurturance. CMT refers to the specific ways/techniques we can use to help us experience compassion, and develop the various aspects of compassion for self and others (Gilbert & Irons, 2005, Gilbert & Procter, 2006)

Mental Distress and Psychotherapy

The development of compassion focused therapy has been a main aim and focus of the Foundation. If our relationships with each other can be marked by a cruelty and a lack of compassion then so too can are relationships with ourselves. Indeed, in regard to our own relationships with ourselves (what we think and feel about ourselves), there is increasing evidence that these can be textured by shame (Gilbert, 1998) and selfcriticisms (Gilbert & Irons, 2005; Zuroff, Santor & Mongrain, 2005). Furthermore, when selfcriticism is associated with anger and selfcontempt there is an elevated risk of psychopathology (Whelton & Greenberg, 2005). Recent psychological interventions have been aimed to try to teach people how to develop selfcompassion as an antidote to shame and self criticism (Gilbert 2000, Gilbert & Irons, 2005). Early studies suggest that this focus is helpful for some people (Gilbert & Proctor, 2006).

Why a Compassion Focus?

Compassion focused therapy was developed for people with chronic mental health problems. They often come from neglectful or abusive backgrounds, have high levels of shame, and are often selfcritical, selfdisliking, or selfhating. As a result they live in a constant world of internal threat (e.g., fear of, or feeling overwhelmed by their own emotions or thoughts, selfcriticisms and selfdislike) and external threat (that others could easily turn against them, condemn them, turn abusive/exploitive, or reject or abandon them). In other words, both the internal world and the external world can be experienced as threatening, with nowhere that is safe.

Such individuals often have few experiences of feeling safe or soothed and are not able to do this for themselves. Indeed, feeling safe, reassured or cared for can actually be (at first) threatening for them. These individuals often do poorly in therapy trials. They are likely to understand the logic of various interventions but have difficulties feeling these as helpful.

Given that some people have difficulties in feeling safe, being kind, gentle, reassuring, accepting or forgiving of themselves CFT and CMT were developed from other therapeutic approaches (both Western and Eastern) to specifically target the development of selfsoothing and selfcompassion. These aim to reduce the sense of threat, and inner hostility to self, and promote acceptance and kindness conducive to wellbeing. Although CFT was developed with people with these kinds of difficulties, clinicians working with a range of different problems (such as trauma, eating disorders and psychosis) have noted major benefits when they texture their traditional practises with CFT.

Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) focuses psychological interventions (e.g., cognitive, affective, behavioural and interpersonal, and use of the therapeutic relationship) to the tasks of illuminating the functions of shame and selfcriticism and developing selfcompassion and compassion for others. It is not a new school of therapy but a focus for therapy (and other social phenomena) that is based on an integrative approach informed by:

1. Evolutionary psychology that helps identify:

Evolved needs (e.g., for safeness, attachment and belonging); evolved emotional and motivational systems (e.g., for threat detection and response, and for relationship building) and evolved competencies (e.g., for selfawareness, identify formation and empathy and theory of mind).

Neuroscience research on genetic and physiological systems that illuminate: basic, specific processes and systems that underpin these evolved processes (e.g., how threat systems work, how affection affects brain development; how affect systems are organised; the role of the frontal cortex in affect regulation).

Research on the functions, processes and change mechanisms of psychological phenomena: Conscious and nonconscious processing, implicit and explicit processing, selfidentity formation, conditioning, rule learning, attitude and belief formation.

Research on cultural, social and interpersonal processes that give shape to: Evolved mechanisms, physiological processes and psychological phenomena (e.g., phenotypes). These include family and peer relationships, cultural values and relating styles and the therapeutic relationship.

Thus CFT is a wide ranging, integrative approach that depends on the emerging ‘science of mind.’ The basic axioms and processes of CFT are not static but ever changing in the light of scientific findings.

The aim of CFT is to help people who are burdened with shame and engage in harsh self criticism, relate these to as understandable safetyfocused, protection strategies, and develop the various components of selfcompassion that promotes wellbeing. CFT helps people formulate problems into: Early background influences (e.g., neglect and abuse) that shapes key fears and concerns, and may have thwarted basic needs (e.g., for secure attachments and affection) and thwart forms of goal seeking. Such experiences can lead to the development of safety strategies (e.g., social avoidance or being excessively submissive and otherpleasing, or aggressive self promotion). These safety and protection focused strategies can lead to unintended consequences and symptoms. CFT helps people develop insight into these linkages between backgrounds, safety strategies and unintended consequences, and then develop empathic and sympathetic understanding, and selfcompassion for these processes.

Compassionate Mind Training (CMT) refers to the many practices (e.g., thought focusing, behavioural practices, exposure, imagery and styles of the therapeutic relationship) we can use to develop our minds to experience and develop compassion for self and others.

Buddhist and Social Psychological Approach: Neff (2003ab), from a social psychology and Buddhist tradition, sees selffocused compassion as consisting of bipolar constructs related to kindness, common humanity and mindfulness. Kindness involves understanding one’s difficulties and being kind and warm in the face of failure or setbacks rather than harshly judgmental and selfcritical. Common humanity involves seeing one’s experiences as part of the human condition rather than as personal, isolating and shaming. Mindful acceptance involves mindful awareness and acceptance of painful thoughts and feelings rather than overidentifying with them. In Buddhism compassion grows from a desire to develop compassion and the practice of mindfulness. Allen and Knight (2005) note that mindfulness and compassionfocused work can be combined in the treatment of depression and other disorders.

Cognitive Approach: McKay & Fanning (1992), who developed a cognitive based self help program for selfesteem, view selfcompassion as involving understanding, acceptance and forgiveness.

Dialectic Behaviour Therapy: Linehan (1993) integrated cognitive behaviour approaches with those of Zen Buddhist concepts and practice. DBT focuses on the importance of validation of people’s (and our own) emotions and experiences, the development of ‘wise mind,’ the abilities to be with and tolerate painful feelings and memories, and self soothing.

Shame and CFT

Psychological therapies are becoming more process rather than ‘school’ focused. Thus we are developing therapies that help us assess various specific difficulties such as ruminations, avoidance, traumatic memories (Harvey, Watkins, Mansell, and Shafran (2004). Shame and selfcriticism are also specific types of psychological process and are associated with a range of psychological difficulties, including depression, social anxiety, eating disorders, various personality disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Gilbert & Irons, 2005). Over a number of years we have worked with people for whom high shame and selfattacking can be hard to work with and change. CFT has therefore emerged from efforts to understand these processes, contextualise them within a neuroscience and evolutionary framework, and develop specific interventions.

As noted above CFT views shame as related to threat processing and distinguishes two types of threat: External and internal. External threats are threats that are perceived to lay outside of the self such as from the actions of others towards the self. Internal threat relates the emergence of internal experiences that negatively impact on selfevaluations, selfidentity selfpresentations and selfcontrol. Shame based selfcritical processes (e.g, I am no good; nobody will care about me) are thus both responses to threats and sources of threat.

CFT therefore considers some of the complexities of threat processing and how to derive formulations based on threat processing and safety strategies. Understanding shame and selfcriticism, as ways to try to defend ourselves via safety strategies such as avoidance, compensation or concealment, are key to compassionfocused formulations.

Over the years various therapies have developed interventions (such as exposure and other techniques involving metacognitive processes) specifically aimed at toning down negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, fear and sadness. Until recently it has less commonly been the explicit focus of therapies to tone up or foster certain types of positive emotions. One of the difficulties in doing this is the lack of clarity concerning the different types of positive affects. One cannot assume that by reducing negative emotions the positive ones will come on line.

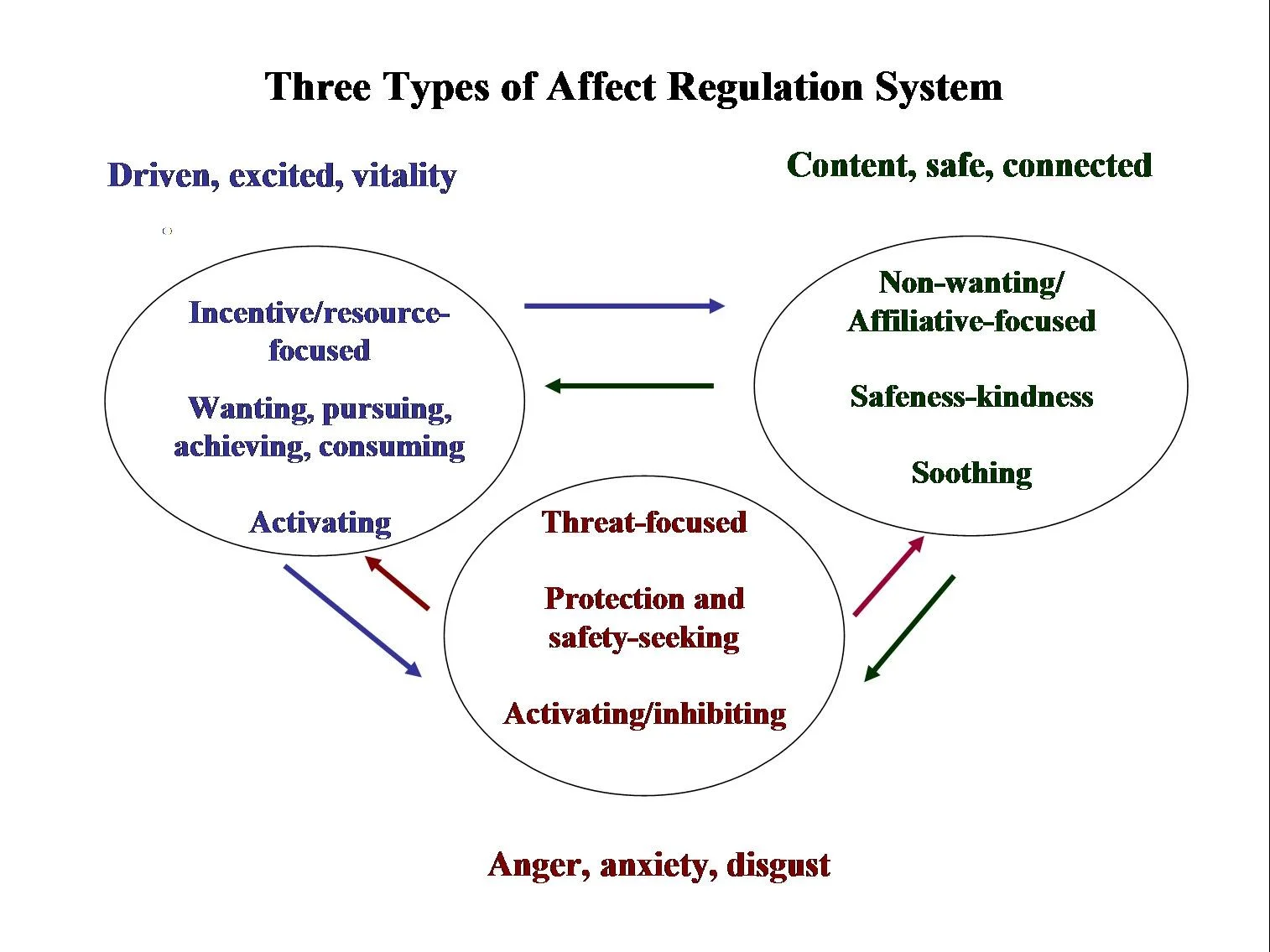

Types of Affect Systems

If we are going to focus on the feelings of selfcompassion and selfsoothing then we need to know soothing about the evolved mechanisms and underlying affect systems that make such feelings possible. Research from neuroscience (e.g., see Depue & Morrone Strupinsky, 2005) suggests that there are at least two very different types of positive affect systems. These relate to:

Drive, vitality and achievement: These are related to the activation of the dopaminergic system.

Affection, soothing and contentment: These are related to the activation of the oxytocin/opiate system.

These are of course very simplified ways of thinking about complex systems. Moreover, they are in constant interaction generating various patterns of activity in our minds. So think of them as ‘rules of thumb’. Nonetheless, this three circle model can be useful in thinking about and guiding your therapy. CFT suggests that some people require help to develop, activate, and feel certain types of positive affect, and without this they may struggle to develop self and otherfocused compassion.

Experiencing The Helpful

Many cognitivebehavioural focused therapies help people distinguish unhelpful thoughts and behaviours that increase or accentuate negative feelings and alternative helpful thoughts and behaviours that do the opposite. This approach works well when people experience these alternatives as helpful. However, suppose a patient says “I can see the logic of thinking like this, and this should feel helpful, but I cannot feel reassured by these alternative thoughts” or “I know that I am not to blame but still feel to blame”.

This is called the headheart lag (Lee, 2005) or cognitionemotion mismatch (Gilbert, 1989). In fact there are many forms of cognitionemotion mismatch when feelings and thoughts do not seem to cohere (Haidt, 2001). For example, research has shown that you can prime an emotion nonconsciously and lead people into false beliefs about why they are feeling what they are feeling (Haidt, 2001). So why do people logically know one thing but can’t feel much reassurance or relief for this knowledge? Well there are many reasons. For example some psychodynamic therapists suggest that selfattacking is actually related to unconscious desires to attack others but being frightened of these feelings. They use Nietzsche’s idea the noone attacks themselves without a secret wish for vengeance. Not until these otherattacking impulses are acknowledged and worked through will selfattacking reduce. This may hold for some people but in fact research suggests that selfcritical people can also be rather harsh on others too.

Another way to think about this the problem may be that their soothing systems (that give us the feelings of reassurance, safeness and soothing) simply do not register the alternative thoughts as helpful. There can be many reasons for this. For example ‘changing one’s mind’ is seen as too threatening or there may be powerful classically conditioned threat responses to feelings of warmth or care; or there may be unresolved traumatic memories. Another major reason is that the opiate/oxytocin soothing system that codes for safeness is insufficiently stimulated and thus they do not feel reassured. Some people have never really felt safe, find those feelings odd, threatening or not to be trusted. The emotional systems that give rise to feelings of reassurance are not active enough or the threats are so great that the threat system overrides them.

Key message: We need to feel congruent affect in order for our thoughts to be meaningful to us. Thus emotions ‘tag’ meaning onto experiences (Greenberg, 2002). In order for us to be reassured by a thought (say) ‘I am lovable’ this thought needs to link with the emotional experience of ‘being lovable/loved’. If the positive affect system for such linkage is not activated there is little feeling to the thought. People who have few memories/experiences of being lovable may thus struggle to feel reassured by alternative thoughts about the self.

Understanding Soothing.

Soothing is a complex and multicomponent process. It is intimately linked to the threat system and help regulate it. So feeling soothed involves a complex interaction between soothing systems and threat systems. As noted in diagram 2, there is a separate emotional system that is sensitive to various cues of care, affection, affiliation and belonging. Hence feeling safe, reassured and soothed can arise, not just via the absence of threat cues that suggest a threat is absent or moving away, but from more specific cues that activate the soothing system. The focus is thus on cues that help us feel safe and that threats are manageable. Basic soothing cues are of course closeness to a supportive other, and physical affection cues such as physical touch, cuddling and hand holding, with evidence that these can affect the opiate systems. Nonverbal communication (facial expression postures and attentiveness) that is picked up in basic affect processing systems in the brain can be key to soothing. However as children grow they increasing feel soothed by others via what they think in is the minds of others. Here are some key aspects:

Social referencing. A child may be anxious about approaching a potential threatening or novel stimulus and looks to the parent to see how they are feeling about the stimulus. The parent displays interest and approaches the stimulus, or may interact with the stimulus in a positive, low fear way. They may also encourage the child to come and explore the stimulus. Thus reassurance here arises from a form of social referencing and modelling. A more complex example is when a person is able to socially reference their own feelings and discovers that others either have the same types of feelings as they do and are not alarmed by them.

Living in the mind of others. Our abilities to feel safe in the social world often come from experiences of how we feel or think others feel and think about us. When we interact with others, so that they show pleasure in our presentations and liking then we can feel safe. In fact people spend much of their time thinking about other people’s feelings towards them, have special cognitive systems for thinking about what others are thinking (called theory of mind) and many of our goals are orientated to try to earn other people’s approval and respect, and be accepted in groups. If you think about how you would like your lovers, close friends, counselling peers, patients and bosses to see you – it will mainly be to value you and see you as desirable, helpful, talented and able. If you can create these feelings in the mind of others then three things happen. First, the world is safe and you can know others will not attack or reject you because they value you. Second, you will be able to cocreate meaningful roles for mutual support, sexual relationships and sharing. Third, receiving signals of others as valuing and caring of you has direct effects on your physiology and soothing system (Depue and MorroneStrupinsky, 2005). Many patients are of course frightened of how they live in the mind of others and that others view them as odd, weak, inadequate or bad. It is changing these internal representations of “how I exist in your mind’ that can be experienced as soothing. In more everyday interactions we can feel unsafe when we think others see as competitors, weak and exploitable or only agents that can be manipulated to serve their own interests. In these contexts we may become highly defensive. Thus we can feel safe when others show that they seek to develop genuine cooperation, that is fair and respectful.

Being heard and understood. Many people can feel threatened and become defensive when they think that others to do not understand them and/or have little interest in ‘hearing them’ or taking their point of view into serious account. We can feel soothed when we feel the opposite – that others sees our views as something to be articulated and are valid and important – not to be overridden or dismissed. This need can take precedence over more physical acts of soothing. For example a patient became upset and tearful. To this her husband would often try to sooth her by putting arm around her. He felt hurt when she tried to push him away. Her account was that she felt he was saying ‘there there’ and trying to quieten her feelings rather than active listening to her concerns and giving her a chance to express herself and be understood. For her, to have someone really listen, and be with her in her distress, was soothing.

Empathic validation. This involves the experience that another mind/person understands our feelings and point of view and that it is understandable to them. Thus a therapist might say “losing you husband like that must have been a horrible experience for you; your depression makes a lot of sense because.........” Empathic validation means that a) we have understanding of the other person’s point of view and connect to it because we can connect to our own basic human psychology – the other is not an unfathomable alien and; b) validation means that we validate their lived experience as genuine, and makes sense as part of the human condition. Thus empathic validation is more than reflection (e.g., ‘you feel sad or angry about this), but acknowledges this as an understandable and valid experience. Once again however empathic validation begins via our experience of how we exist in the mind of others. Invalidation can be “you should not feel like this, this is neurotic, you are exaggerating; you have no need to feel like this; you are being irrational etc). Many conflicts in the world can arise when people feel others are invalidating them through lack of interest, efforts to understand them or care.

Many people have a complex of feelings that may be difficult to understand and of which they may be fearful of (Leahy, 2002). They may cope with this via avoidance, denial, dissociation or replacing one feeling with another. Socially referencing, being listened to and empathic validation are important experiences of ‘what is going on in the mind of the other’ that helps a person come to terms with, and understand, their own feelings. Patient and therapist work out together the ‘basic feeling issues’ and help the person be aware of and address emotional memories, unmet needs or key fears that might make feelings frightening.

Reasoning. CBT puts a lot of emphasis on reasoning. When we feel threatened the attention narrows down onto the threat and we shift to better safe than sorry thinking. We can feel soothed when we are able to stand back and examine our thoughts in detail and come to a different perspective. Although it can happen that we can ‘work things out for ourselves’ as children we first learn how to reason but observing others, and developing our to be in line with their values. Also parents and teachers may offer direct instructions on how to think about this or that. In many ways CBT therapists are helping people with these processes of thinking and reasoning in the face of strong emotions or fears. Thus the degree of change may be how far the therapists can persuade or encourage a person to look more deeply at their reasoning and experiment with alternative views. Processes that help us deescalate threats or cope in new ways can affect soothing and reassurance

However being able to deescalate a threat in our minds through reasoning may not necessarily sooth us in the sense that we feel safer, connected and have a sense of belonging. Some people may feel able to do this ‘cognitive work’ but still have an inner sense of emptiness or coldness. The most important meanings in our life arise from social goals and those connected to them (e.g., feel loved, wanted, cared about and esteemed by others). Reasoning is thus obviously very helpful and important to how safe or threatened in the world we feel, but soothing and feeling more generally safe in CFT has a more social aspect.

Desensitisation. Key to many behavioural approaches are those linked to forms of exposure and desensitisation. In some cases coming to feel safe requires that we are able to experience both internal and external fears in new ways. Thus in CFT the ability to ‘stay with’ and learn to tolerate frightening feelings or situations can be key to soothing. However just as the child may use to parent to navigate these domains so may a patient need to feel ‘held and contained’ by the therapist during the process. The inability to trust others may be a key reason why people become resistant to engaging in these processes – because they feel they have no safe base. In fact a key ingredient of successful behaviour therapist may be the way the therapist is able to encourage, hold and contain the anxieties of their patients as they engage in various exposures.

Psychoeducation. Many focused therapies today involve psychoeducation. Compassion focused therapy suggests that because we have evolved brains that are working out basic strategies (with phenotypes), education on basic psychological process are extremely helpful to offering people frameworks for thinking about their difficulties, deshaming them and offering sign posts on how to move forward. For example we discuss the nature of our evolved threat systems and how all living things are designed with basic self protection systems; we explain the nature of the three affect systems of diagram 2; and we explain the nature and purpose of compassion focused work. Via education people are more able to engage in the therapy as active collaborators.

Overview

Compassion focused therapy was developed to help people develop emotionfocused experiences of selfsoothing; i.e., to tone up this type of affect so that it can be readily accessed and help regulate threat based emotions of anger, fear, and disgust and shame (Gilbert 1989, 2000, 2005, in press.) Clinical and research work suggests that some people, especially those who have experienced early histories characterized by abuse and neglect, can have great difficulty in being able to access the soothing system. Not only may people have many experiences of being under great threat from others, but few experiences of being or feeling protected, safe and/or soothed by others. In consequence they are unable to selfsooth themselves (Gilbert & Irons 2005, Gilbert & Procter, 2006)